Overpopulation, lack of hygiene and epidemics

With the progress of civilization and the increasing of people to be fed man is increasingly looking for new areas to be cultivated. One of the means which is more within reach is cutting down the trees of tropical forests and burning them on the spot to get cultivable soil.

In many zones, particularly in North Africa, where now there are deserts, there were luxuriant gardens. The need of wheat and construction timber of the ancient Romans had entire forests be destroyed and over the centuries they haven’t reproduced any longer.

The intensifying of slash and burn cultivations and the progress of civilization generally drives man into a direct contact with viruses and bacteria, which would be otherwise inacessible, of animal reserve.

At the beginning of their history the Romans had no sewer systems and in their primitve city population would drink the water of wells and of the Tiber. The stocks of wheat, somehow stored, were at mice’s disposal the number of which greatly increased.

Plague epidemics appreared very soon and either medicine or other remedies could nothing. Over time the Romans worked out a very precise idea of personal and environmental hygiene. Sewers, aqueducts, thermal baths were built everywhere. Even today the remains of these constructions may be admired in every corner of what was the Roman Empire. The Romans knew the close relation between lack of hygiene and epidemics.

An example may be the little town of Bath, which means bagno, in South England where the Romans had built very nice thermal baths.

The “cultus” was the sacred duty for every citizen to keep his own body clean and decent.

Somebody may object poor people lived in unhealthy houses, but actually they would spend a lot of their time at the forum or at the thermal baths where, like the ones of Caracalla, the water of tanks was changed about twice a day[2].

When during military campaigns, the army occupied a place for more than three days, the Romans would immediately build simple latrines and sewers because they had sensed that after that period of time the pollution of the soil and the risk of diseases were inevitable.

A particular care was devoted to the construction of granaries and depots for foodstuffs.They were wetproof, worm and mouse proof.

With the decline and the end of the Empire, all these hygienic systems disappeared, streets became sewers in the open air and houses hadn’t a direct water supply any longer. At the same time the plague linked to fleas and rodents starts its triumphal career.

This was more or less the situation in London in 1665, the year of the Great Plague. Something even more important is the fact that London houses often had thatched roofs, this way they offered a very good refuge for mice, while fleas, where they were sheltered, could fall down the houses below where men lived.

Therefore how being amazed, if a disease the agent of which, the Pasteurella Pestis, has mice as primary guests and fleas as intermediate ones, had been raging for centuries?

It will take many years since that terrible 1665 in London so that Edwin Chadwich from England could think of a simple system of collecting filthy waters and bringing running water inside the houses[3].

Chadwich’s dream failed for economic and privacy reasons. This happened in London nearly two thousand years later when in Rome there was already a very efficient sewer system[4]. And yet London, Chadwich’s city, had been founded by the Romans who had called it Londinium.

Man’s attempts of opposing epidemic diseases were a lot, but till the end of ‘700 the results of medical intervention were scarce or of no use. Gian Giacomo Casanova, in his Memorie wrote “More people die in doctors’ hands rather than the ones who are cured by them”.

[1] Penso G, La medicina romana. Pag 508 Giba Geigy Edizioni 1985.

[2] So much hygiene mustn’t have been liked by the Goths, a barbarian people, because, when in 537 they invaded Rome, the first thing they did was cutting the Antoniano aqueduct which fed Caracalla thermal baths.

[3] Mc Neill W H, Plagues and peoples. Pag.240-41 Anchor Book Doubleday New York 1989.

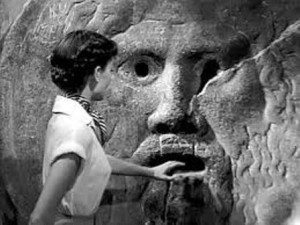

[4] Even some manholes of the sewer system were decorated with mosaics, geometrical figures or masks like the famous mouth of truth we can see in the Church of Santa Maria Di Cosmedin in Rome.

Translated from “Il Virus Intelligente” by Enrica Narducci

About the Author

Written by Ferdinando Gargiulo

Ferdinando Gargiulo offers you a new perspective on why new viral epidemics, assaults, infanticides, suicide epidemics and even environmental catastrophes. Always engaged in his research decides to create a blog to offer his readers content of high value.

Search

Recent Post

Follow on Facebook

Find us on Google Plus

Follow on Twitter

Stories Archive

- Blog (132)

- child labor (10)

- child Prostitution (6)

- Climate Change (20)

- depression (53)

- Depression and suicide (51)

- Environmental catastrophes (22)

- epidemics (44)

- Genetic hypothesis of suicide (47)

- HIV (24)

- Leonardo Da Vinci (8)

- overpopulation (108)

- pedophilia (7)

- Serial Killer (33)

- Suicide Genes (46)

- suicides (56)

- The child as a product (10)

- the intelligent virus (106)

- Uncategorized (59,869)

- Unexplained aggression (36)

- You Tube (6)